The medical decision–to have a screening mammogram, to take warfarin, to undergo a catheter ablation–is, at its core, a gamble. We pit the treasure of the win (benefit) against the pain of the loss (harm).

In times past, medical gambles were easier. You took the antibiotic or you lost your leg. Most medical decisions today are hardly that clear. We say they are preference-sensitive.

Many factors determine these preferences.

The digital revolution notwithstanding, what a patient prefers turns substantially on how the decision is framed. (Wear this vest or you could die.) How the decision is framed depends on the doctor’s preferences. What a doctor prefers turns on how key opinion leaders and policy people think. (Get blood pressure to this level.) How key opinion leaders and policy people think depends on a lot of things, maybe even their industry relationships. And so on.

It is like a symphony of human behavioral psychology. A gumbo of bias. (Grin.)

I read two articles today that made me think about the act of deciding things in medicine.

Drs. Aaron Carroll and Austin Frakt wrote in the New York Times today about the way we measure a treatment’s potential for harm. I am drawn to this sort of work because harm avoidance is a core feature of heart rhythm care. Their pictorial of the benefits and harms of screening mammograms underscores something I preach everyday: all medical decisions are a gamble.

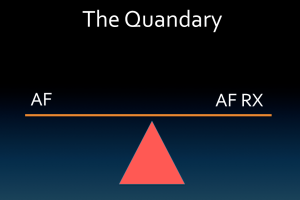

Here is the risk quandary for AF:

Dr. Scott Aberegg is a medical doctor in Utah who writes the Medical Evidence Blog. In this post, he takes an interesting view on how the NNT (Number Needed to Treat) statistic can get patients into a Therapeutic Paradox–where what is good for the population may not be good for the individual. (e.g. the voter’s paradox).

Treatment A offers you only a 0.1% chance of benefit. But that tiny fraction adds up if applied to a population of millions. When I questioned the benefits of statin drugs for primary (not secondary) prevention, more than a few commenters used the population-benefit argument. And they are right, sort of. The problem is that populations do not sit across from doctors in the exam room.

It gets back to the symphony of decisions. Health policy leaders–those who influence doctors–might see the gamble of certain treatments from a different perspective than a person swallowing the pill. I like this quote from Dr. Aberegg:

“if we treat 33 people with coumadin, we prevent one stroke among them…A person trying to understand stroke prevention with coumadin could care less about the other 32 people his doctor is treating with coumadin, he is interested in himself.”

Dr. Sergio Pinski’s response to my Tweet captures the essence of the doctor’s role. I referred to the power we hold as framers of the gamble.

@drjohnm @EJSMD we are choice architects.

— Sergio Pinski (@SergioPinski) January 27, 2015

Architect (second definition) — a person who is responsible for inventing or realizing a particular idea or project.

When doctors discuss and recommend actions, they engineer a choice.

When patients decide to have the test or take the treatment, they enact the wager.

Does everyone understand the odds? Are we clear about who wins and who loses?

More important, and this is key:

Do we even think of this act as a gamble?

JMM

P.S. Here are 146 other reasons to see the medical decision as a gamble.

H/t to The Healthcare Blog, who reposted Dr. Aberegg’s piece.

4 replies on “The medical decision as a gamble”

I have some background in probability and statistics, so this post resonates with me.

I’m with this guy (teach statistics before calculus!):

http://www.ted.com/talks/arthur_benjamin_s_formula_for_changing_math_education

I love the section at the end of this post. What a contrast to the vaccine posturing (from both sides) that buries my twitter and news feeds today.

It all boils down to an argument about who takes the risk and who wins and loses.

Nice post John! The equation should be described in terms of potential for benefit vs potential for harm. Would be a clear way to emphasize that there is no guarantee that anyone following an intervention will improve …

Dear John

Another well written article, thanks.

You might be interested in the Dartmouth Atlas which tracks outcomes.

Jack Wennberg did pioneering research on this when he noted his son’s pediatricians declared it was time to take out the tonsils despite no illness!

He surveyed pediatricians the next town over who never recommended surgery for a non disease state (the presence of tonsils and adnenoids).

This started him looking into why some doctors push for this or that treatment and others do not.

Dr Gilbert Welch has taken over as the famous outcomes research physician there. He is often quoted when the latest mammogram results come out.

His books are : ” Should I be tested for cancer? Maybe not and here is why”

and “Overdiagnosed : making people sick in the pursuit of health”

http://www.amazon.com/Overdiagnosed-Making-People-Pursuit-Health/dp/0807021997

Cheers

Tom

Your title hit a note with me. Several years ago, Mike Lesch (of the Lesh-Nyhan Syndrome) was the Chief of Cardiology at Northwestern Memorial hospital. He was fond of telling his patients that he was essentially their “bookie” – a very sophisticated bookie to be sure, but he was making recommendations based on odds and he was always sure to be open to sharing what odds he was basing recommendations on and where the odds came from.

I always believed that Mike was ahead of his time, sounds like you are confirming that. Lack of hubris and transparency went a long way to helping SOME patients then and continue to help patients today. Some patients didn’t then and don’t now want to be participants in the medical decision – they want to be told what to do.

One of our challenges in the future will be to identify which patient we are dealing with (and not be judgmental), accept that patient’s decision making process and then give enough information in a way that the patient will really understand the decision that is being made with/for them.