Cardiology is on the brink of making a big mistake. We have embraced a new procedure called left atrial appendage occlusion.

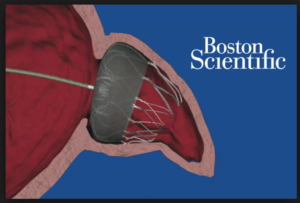

You may be seeing the ads for a device called Watchman. Like this one>

The appendage-closure idea was a good one: during atrial fibrillation (AF), blood can pool in the left atrial appendage, and this promotes clot formation. (The LA appendage has many nooks and crannies.) So… if we could put a device in there, see image, this would block clots from getting out and causing stroke. Also, once  the device has been in for months, the body walls it off and the patient can stop the anticoagulant drug (warfarin, or one of the new drugs, called NOACs).

the device has been in for months, the body walls it off and the patient can stop the anticoagulant drug (warfarin, or one of the new drugs, called NOACs).

Here is the problem: The Watchman device does not prevent strokes. When compared in the best test of medicine, the randomized controlled trial (RCT), the device was inferior to warfarin.

Another problem: advocates for the device have used selective reporting and publishing of trial results to alter the way patients and doctors perceive reality.

This week I published a detailed critical appraisal of the evidence for Watchman.

Here is the piece: Left Atrial Appendage Closure Should Stop Now.

The three take-home messages from that post are:

Take-home #1: In the first trial of Watchman v warfarin, called the PROTECT-AF study, complications were high. This finding, plus other irregularities led the FDA to reject the device and call for another trial.

The second trial of Watchman v warfarin, called the PREVAIL study, showed lower complication rates (good), but higher rates of ischemic stroke (the kind caused by clots) in the Watchman arm.

Take-home #2:Â The tricky part of the selective reporting of Watchman began with the PREVAIL trial.

Here, the authors of PREVAIL published the paper (2014) with incomplete results–only 28% of patients had reached the 1.5 years of follow-up. In this very early look at the data, the results looked nearly equivalent, though there were still more strokes in the Watchman group.

Two months after that paper was published, the PREVAIL investigators reported longer-term follow-up from the study at a medical meeting and to the FDA. (Neither of which shows in PubMed searches.)

This new data showed 8 additional strokes in the Watchman arm and none in warfarin group. Now the PREVAIL study totals were 13 strokes in Watchman versus 1 in the warfarin group. With this new data, the endpoints of PREVAIL were NOT noninferior. Or, in clear language, inferior.

Yet, crucially, this updated data, which would turn the pivotal trial for this device negative, have not been published. Instead, the authors decided to publish a meta-analysis of multiple studies of Watchman, including softer registry studies.

By combining this mishmash of studies (meta-analysis) and by using a composite endpoint, the authors noted noninferiority of the device. But even in that meta-analysis, if you look at strokes due to clots, the results show more with Watchman.

It gets worse.

Not only is the more complete PREVAIL data not published, but leaders in the field of cardiology, including influential guideline writers, continue to cite the 2014 study that is published as noninferior, but is really inferior–if it had been updated. A reader of the published literature, therefore, would think the device is equivalent when in fact it is not. Even the majority of the FDA reviewers felt the device did not meet its efficacy endpoints.

Not only is the more complete PREVAIL data not published, but leaders in the field of cardiology, including influential guideline writers, continue to cite the 2014 study that is published as noninferior, but is really inferior–if it had been updated. A reader of the published literature, therefore, would think the device is equivalent when in fact it is not. Even the majority of the FDA reviewers felt the device did not meet its efficacy endpoints.

A literature search in PubMed for two of the more prominent authors of the non-updated PREVAIL study and “Watchman,” shows 10 papers since the 2014 incomplete paper. One wonders why this important data has not been published. Could it be that it would turn the pivotal trial for Watchman into a negative trial?

In my post, the primary investigator of the study, Dr. Vivek Reddy, explains why that data is not published. It’s a complicated statistical explanation.

Take-home #3:Â What about patients who can’t take anticoagulant drugs?

Proponents of the technology say we should use the device for patients who cannot take anticoagulant drugs because of bleeding. It’s true; for patients who have had AF, stroke, and bleeding, there are no good options.

But these patients were not included in trials with Watchman. That means we don’t know the device would work. The signals thus far suggest the device would not help these patients. For one, it doesn’t protect against stroke relative to warfarin. For another, even if it did reduce stroke by 1-2%, this benefit would be balanced by the 2-3% complication rate of implant.

What I believe should have happened for these difficult patients is the device been approved but only as part of a study. Nearly 4000 patients in the US have had this device, and if they were in a clinical trial, we’d be well along in knowing whether this device helps people who cannot tolerate anticoagulant drugs.

At the root of our embrace of this technology is the desire to help patients. But that benevolent drive should not blind us to the evidence.

Here’s the slide I usually start my critical appraisal talks with:  JMM

JMM

6 replies on “Say No to Watchman”

I remember months back I read that “most” afib clots form in the LAA. Most. So I guess this means that “many” form in other areas of the heart… enough to make Watchman inferior to Coumadin. I have a few questions:

1) Do they have an idea of what percent of afib strokes form in other than the LAA?

2) Could closing off the LAA actually “cause” clots to form elsewhere?

3) Would having closure of the LAA and an anticoagulant together be the ultimate protection?

4) Would the installation of the Watchman preclude using Dabigatran as is the case with artificial heart valves?

5) How does closing off the LAA affect pressure inside the heart?

6) What are the long term effects of having a mechanical device in the heart? It would seem that preventing strokes with a pill is better than having something mechanical in the heart, particularly if it “fails” in some way like the other implanted devices such as are used in hip replacements.

7) What will happen to those that already have these devices implanted?

“Nearly 4000 patients in the US have had this device, and if they were in a clinical trial, we’d be well along in knowing whether this device helps people who cannot tolerate anticoagulant drugs.”

Exactly.

Take a look at this study, hats off to thr authors for digging the truth in their meta-analysis (using FDA documents). Watchman is the worst

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0163608&fullSite

Answer on the posting of Mandrola “Left Atrial Appendage Closure Should Stop Nowâ€

of Nov 10 at Medscape

We agree with the position, that the latest series of 3,822 Watchman cases presented at the TCT, was a non-adjudicated one, secondarily captured and reported by others than the implanters. Therefore, the periprocedural safety results may have been underreported.

Certainly, safety remains a problem of LAAC and needs to be weighed-out against the risks of lifelong anticoagulation or no anticoagulation in each eligible patient.

Today, peri-procedural safety rates of 2-3% are already achievable and have been shown for the Watchman device (EWOLUTION registry, Boersma et al, EHJ 2016 and the AMPLATZER: The AMULET Study, Hildick-Smith, TCT 2016).

In other words, if a patient has a residual life expectancy of >3 years, LAAC will provide a net clinical benefit over anticoagulation, i.e. from the mid-term and surely in the longer term, LAAC will offer a better protection form all hazards a patient with AF is exposed to, namely death, stroke and bleedings due to the need of anticoagulation.

In his post of November 10, 2016, Mandrola concludes that LAAC fails to protect against ischemic events and that it should be stopped now.

In fact, in PROTECT-AF late (which are neither mentioned nor cited in the story of Mandrola, Reddy et al, JAMA 2014), the rate of ischemic strokes was slightly higher in the Watchman group than in the VKA group (24 ischemic strokes per 1721 patient-years, i.e. 1.4% vs 10 ischemic strokes per 904 patient-years, i.e. 1.1%/100 patient-years), missing to proof non-inferiority or superiority. This, presumably may be due to device-related thrombi in this very early cohort of 463 Watchman patients, which included all the learning curves of most operators, rather sparse imaging and an earlier generation of the device.

However:

– In PROTECT-AF late, overall stroke rate was LOWER in the Watchman group (1.5% vs. 2.2%), proofing non-inferiority. This is due to only 0.2% of hemorrhagic strokes in comparison to 1.1% in the VKA group.

– Cardiovascular and unexplained mortality were LOWER (1.0% vs. 2.4%), proofing SUPERIORITY of LAAC with the Watchman against VKA.

Those hard facts led to the approval of the device in Marc 2015 by the FDA and are not mentioned in the Medsacpe article of Mandrola.

In our cohort (unpublished data), which has been treated exclusively with AMPLATZER devices, we recently captured 1422 patient-years of 559 consecutive patients. Despite a significant rate of device-related thrombi of 4.7%, protection from stroke was excellent with 16 ischemic and 0 hemorrhagic strokes in 559 patients after a mean follow-up of 2.5 years, yielding an overall stroke rate of 1.13% (0.5% disabling, 0.7% non-disabling strokes, mean modified Rankin score 1.7, mean NIHSS score 8.5).

This is in line with other data for the Amplatzer device (1.3% in >1000 patient years, Tzikas et al, EuroIntervention 2015) and if compared with the RE-LY study, the only study which proofed superiority over VKA in the full-dose regimen, on the same level.

Therefore, our conclusions are:

– LAAC will remain a challenging procedure with a certain rate of peri-procedural safety events

– Protection from all-cause stroke by LAAC is excellent!

– Offering LAAC to a patient is not only about plugging the LAA, but also to protect her or him from the ongoing hazards of lifelong anticoagulation or no anticoagulation.

– The concept of LAAC works, which is proofed by noninferiority in all cause strokes and superiority not only in cardiovascular and unexplained, but also in overall mortality.

– LAAC should by no means be stopped, but is here to stay and to offer the best possible protection from all hazards of AF, namely death, stroke and bleedings.

Steffen Gloekler, MD, Cardiology, Bern University Hospital

Bernhard Meier, MD, Cardiology, Bern University Hospital

It is an honor to receive such a comment on my personal blog. Thank you.

I did mention PROTECT-AF in the Medscape piece: Here is the quote:

What We Know

To review, the PROTECT-AF trial[2] compared Watchman and warfarin in patients with AF (mean CHA2DS2-VASc=3.5). The results did not pass FDA muster. Although Watchman proved noninferior to warfarin for the primary end point, a composite of stroke, cardiovascular death, and systemic embolism, the FDA had concerns about excess procedural complications. These concerns, plus the confounding effects of concomitant antithrombotic drugs and subjects not receiving assigned treatments, led the FDA to ask for another trial.

At this point, the FDA was correct. If occlusion of the left atrial appendage works it should reduce ischemic stroke and systemic embolism. Yet a review of the primary end points from table 2 of the PROTECT-AF Lancet publication reveals a 50% higher rate of ischemic strokes plus systemic embolism in the Watchman arm (17/463 vs 6/244). Increasing the concern from this signal of inefficacy is the fact that 15% of patients in the Watchman arm remained on anticoagulation.

Here is another comment to consider on PROTECT-AF:

“Neither PROTECT-AF nor PREVAIL were powered for individual components of the composite endpoint. Hemorrhagic stroke was double counted as an efficacy endpoint and also safety endpoint. If you exclude hemorrhagic stroke from efficacy endpoint in PROTECT-AF and only count it towards safety, non-inferiority would not be met, despite a wide margin (RR of 2). There were many other problems with PROTECT-AF, hence FDA did not deem it pivotal for approval.”

I understand your point about late events, but from an overall efficacy standpoint you cannot exclude the early events.

I also don’t think overall stroke is a good endpoint. Of course hemorrhagic stroke will be less in the arm that does not take anticoagulants–the Watchman arm. If ischemic stroke is increased in the Watchman arm, as it was in PREVAIL, and in the meta-analysis (Holmes et al), than the device is not any more useful than just not using anticoagulants.

Finally, I applaud your center’s registry but like all registries, there is no control arm. So, yes, your stroke rate is low, but you don’t know what it would be without a control. What’s more, an untreated control would not incur the 4-5% device thrombi rate or any device complications.

I’m sure that we agree on the need for an RCT of device versus no anticoagulation in the anticoagulation-ineligble patient.

So as a RN and NP student wishing to go into cardiology and avid follower of your posts, I show your Medscape article to a superb cardiologist performing TEE’s today in 5 patients planned to be the launching pad for our new Watchman program. The reaction was true, true, and I agree. However guess what were doing…. The Oxford dictionary’s 2016 choice for word of the year could not have been more appropriate for the times we live in.